John Wilkinson -

Copper King ?

John Wilkinson – Copper King?

A Review of the Activities of John Wilkinson

in Connection with the Copper Industry by Vin Callcut.

Broseley Local History Society and The Wilkinson Society

Wilkinson Lecture, March 2nd 2005

Summary

Introduction

Wilkinson’s Copper background.

The Importance of Copper to Ironmaster Wilkinson

John Wilkinson’s contemporaries (some only)

Late 18th Century Copper Industry

Copper deposits in UK and Ireland

Production of the main mine areas

Production of the main mine areas

Copper Production 1770-1805

Copper Markets in England in 1790

Inflation in England

British Copper Prices 1770-1805

Copper Price variables

Some Copper Kings

Sir Ronald Prain OBE (1907-1991)

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875-1968)

The Wars of the Copper Kings 1876 – 1905

Paul Revere (1734-1818)

John Vivian

Thomas Williams (1737-1802)

Copper King Qualities

The Modern Copper Age

John Wilkinson (1728-1808)

Quotations re John Wilkinson

Topics continued as: Wilkinsons Interests in Copper

1775 Wilkinson’s Steam Engines

1785 The Cornish Metal Co

Shares in Copper Mines

1788 Birmingham Warehouse Company

Copper in Cast Iron

1787-1793 Wilkinson’s Copper Tokens

A Token Profit?

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Summary

A review of published literature has shown that John Wilkinson had significant interests in many aspects of the British copper industry and was very influential in its development and prosperity. His activities are surveyed in the context of the economic status of the industry. For comparison, there is a brief summary of the activities of some other copper kings. It can be seen that John Wilkinson had many similar achievements and can be considered by Society members to be worthy of the title ‘Copper King’. More information would be welcome regarding details of some of his ventures and the profits made.

Introduction

John Wilkinson developed interests in a very wide variety of projects. Ironmaking was his first priority but his agile mind could see opportunities as they arose or alternatively, make them for himself. On occasions he realised that he had made more money than he could easily re-invest in that industry with advantage. There was plenty of competition from other ironmasters and their ironworks nationwide. He needed to invest outside the industry. He frequently looked for opportunities where his special technical, financial and political skills were of advantage. The copper industry was an ideal choice amongst others.

It has been possible to obtain useful, and background, information from about 70 publications listed in the Bibliography. A main source has been ‘The Copper King’, the excellent biography of Thomas Williams by the late Professor Jack Harris of Liverpool. He makes reference to John Wilkinson on 28 different pages and it is obvious that without him, Williams might not have been as successful as he undoubtedly was. Janet Butler’s thesis contains 40 pages on Wilkinson’s copper interests. Some of this is drawn from Harris and is combined with more from her other research work. Much other useful information is found repeated in different articles with varying detail.

When reading into the subject, it quickly became obvious that John Wilkinson was a leading entrepreneur in the copper industry during his day. With his wide spread of successful interests, his nearest modern equivalent in spirit might be Sir Richard Branson. The question soon arose:

Could he be called ‘A Copper King’?

This review is written from the point of view of a 20th century industrial metallurgist with a strong interest in copper and its alloys. Its aims are:

♀ To appreciate Wilkinson’s background, environment, important business colleagues and operations connected with the copper mining and manufacturing industries.

♀ To summarise the position of the British copper industry at the time being considered.

♀ To appreciate the standards set by other acknowledged Copper Kings and compare Wilkinson’s achievements.

Wilkinson’s Copper background

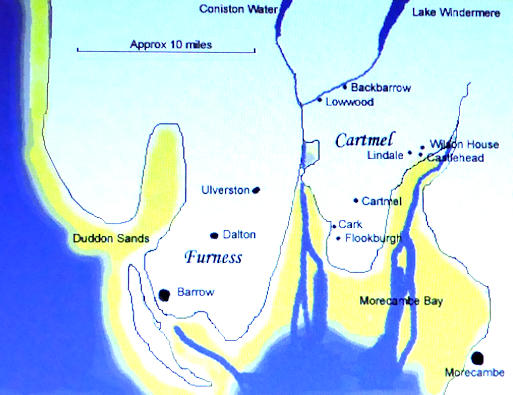

John Wilkinson was born near the border between Scotland and England. The exact position of this border has varied with time and there has been a significant movement of people and goods between the two over the centuries. There are no known Scots amongst his immediate forbears but further back there undoubtedly would have been. At one time the economy of Scotland was partly dependant on copper at times when the Western Isles were on the main copper trade routes between Ireland and Sweden, so copper might well have appeared in his gene pool.

John Wilkinson would have spoken with a Cumbrian accent that would have kept him unaffected by any local interest group prejudices of the time such as may have occurred in, for example, Birmingham, Cornwall, Shropshire, South Wales or North Wales. This would have given him quite an advantage in his business dealings with groups around the country. Interestingly, the name ‘Wilkinson’ is an anglicised version of ‘McQuillan’, a McDonald Clan surname once proscribed by the English. This was the name of a metallurgist of repute in Cambridge during the mid 20th century, Prof. A D McQuillan, who, together with his wife, wrote the first standard reference book on Titanium and its alloys. Perhaps the metallurgical line still runs in the blood. Other links that may be postulated in this paper are far less tenuous!

He was brought up in the Lake District and during his most formative years was educated in Kendal. This is not far from Keswick where The Company of Mines Royal, set up in 1568, had previously extracted copper to meet the national need for strategic materials.

In 1738 his father, Isaac Wilkinson, patented his new design for a one piece casting for a box iron ‘of one entire piece of any cast metal either iron, brass, copper or bell metal. At Bersham there were five furnaces used for casting copper, each of 4 tons capacity that were used to cast a 20 ton copper table. Coincidentally perhaps, in 1761 when Isaac Wilkinson’s Bersham works collapsed, he retired to Bristol, centre of the brass industry, where he might be amongst friends.

The Importance of Copper to Ironmaster Wilkinson

The exploitation and use of copper pre-dated iron in many respects. It is easier to refine due to a somewhat lower melting point. It is also easier to add alloying additions to increase strength and hardness. Much of the technology was transferable to iron making with some upgrading of the methods used. With his excellent grasp of technology, Wilkinson would have been aware of the useful information to be gained from the copper industry.

During the Chalcolithic age, blast furnace design was developed for refining copper and lead. This furthered the understanding and development of good refractories for successful lining of the furnaces, especially so for copper that has the higher melting point than lead.

14th C Wire drawing was developed in Nürnburg, The availability of brass wire was absolutely vital to the wool-based economy of both the Lake District and Shropshire. It was used to make the multi-teeth wire cards used to tease out wool before spinning. Before brass was made in Britain it had to be smuggled in from Belgium and Germany because of import restrictions.

This close up of a modern file cleaning card shows the basic wire shape that was used for the brass wires of wool cards.

16th C Export sales of bronze cannon started in Elizabethan times and continued thereafter.

1697 Early rolling mills for copper and brass sheet were installed by Dockwra at Esher in Surrey.

1698 The reverbatory furnace was developed for reliability at temperature in Swansea. The fuel was not in direct contact with the charge as it is in a blast furnace.

c1700 The use of coal, and subsequently coke, instead of charcoal was pioneered in Abraham Darby I’s Bristol Brass Company.

1714 Steam cylinders for Newcomen engines were initially made of brass. That for the Bilston engine was cast at Bromsgrove Brass Foundry.

1738 William Champion patented in England the method of production of zinc using a retort. Quantity production of cheap brass would now be possible.

1761 Copper cladding for wooden hulled ships was first applied to protect HMS Alarm and then all ships of the Royal Navy and the East India Company giving a very useful extra tonnage market for copper sheet.

1769 Stamping machines were patented by John Pickering in Birmingham.

1780 By this time nearby Birmingham was using 1,000 tons of brass per year.

Brass has long had a good reputation when precision manufacture and long life is needed as with clocks, chronometers and watches. Brass has long been used to make accurate weights. And, of course, Brass means money – it was in Bristol, the centre of the Brass industry during the 18th century, that Wilkinson found the six merchants who helped to provide much of the capital for his New Willey furnace.

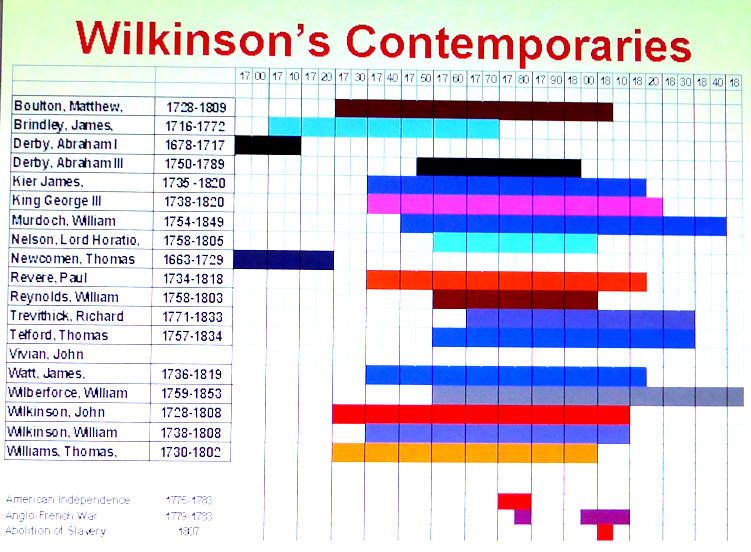

John Wilkinson’s contemporaries

This selective list shows just a few of the many influential entrepreneurs around during Wilkinson’s lifetime. Many were influential in the development of technology and transportation. Other names help the assessment of current times and events. He will have gained inspiration and assistance from his friendship with many of them and others who would have helped to broaden his mind that was ever ready to see where advantages existed. He is frequently mentioned as being willing to help many of his friends.

Wilkinson, John, 1728-1808

Boulton, Matthew, 1728-1809

Brindley, James, 1716-1772

Burns, Robert, 1759-1796

Darby, Abraham III 1750-1789

Darwin, Erasmus, 1731-1802

Dundonald, Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of, 1749-1831

Kier James, 1735 -1820

King George III, 1738-1820

Murdoch, William, 1754-1849

Nelson, Lord Horatio, 1758-1805

Priestley, Joseph, 1733-1804

Reynolds, William, 1758-1803

Trevithick, Richard, 1771-1833

Telford, Thomas, 1757-1834

Vivian, John, ?

Watt, James, 1736-1819

Wilberforce, William, 1759-1853

Wilkinson, William, 1738-1808

Williams, Thomas, 1730-1802

This list includes a selection of industrialists and other notable people to help put the period in context with other events. In addition to the people listed above, he had good contacts with many others including other members of The Lunar Society. Through Samuel Moore, the Secretary of The Society of Arts and Manufactures (now the Royal Society for Arts and Sciences) he had an excellent introduction to the President and all the other members. This was the Age of Enlightenment in Georgian times, when many adventurers and their enterprises prospered.

Late 18th Century Copper Industry

This section summarises the statistics found that cover the relevant period and provides useful background information. Some of the figures may be approximate but they help the assessment of the events mentioned in this paper in the context of the National economy.

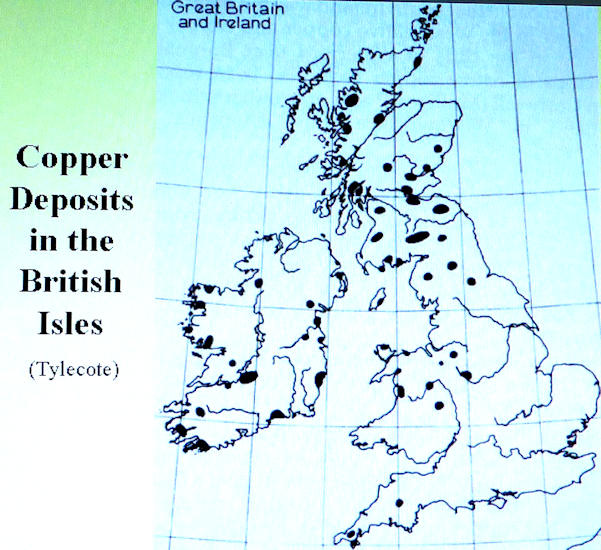

Copper deposits in UK and Ireland

This map is taken from Prof. Tylecote’s book on the pre-history of metallurgy in the British Isles. It shows the widespread availability of copper but cannot cover the grades of copper ores in particular areas. During the late 18th century the main mines being worked economically were in Cornwall, Anglesey and Ireland.

Production of the main mine areas

These are some tonnage figures for production in three main mining areas. They emphasise a sharp decline in production in Anglesey during the 1790s as the easily accessible ores were worked out.

Year |

Tons per year |

||

|

Cornwall |

Anglesey |

Ireland |

1787[1] |

4768 |

4,000 |

|

1792[2] |

|

1,000 |

120 |

1796 |

5,210 |

|

|

1797 |

|

|

|

1798 |

5,600 |

716 |

|

1799 |

|

484 |

|

Copper Production 1770-1805 [1]

Thousands of tons per year

For most of this time, Britain was the largest producer of copper in the world. Towards the end of the period other mines came on stream elsewhere in the World, notably in Spain and Chile. Some had high-grade ore that could be extracted cheaply and imported to the Swansea area economically. This was the time for John Wilkinson to reduce his interest in primary copper and become more involved with copper and brass fabrication industries and chemical plants. He did.

[1] Schmitz

Copper Markets in England in 1790[1]

The figures represented by the pie chart are:

|

Ton/yr |

Birmingham |

2000 |

East India Co. |

1500 |

Navy |

1000 |

Coinage |

600 |

Total British production around this time was of well over 4,000 tons per year including that from the main areas mentioned plus copper from Ecton in Staffordshire, Llandudno Great Orme mine and a few other small ones, some of which were in Shropshire.[2] Exports by East India Company averaged approximately 1,500 ton/yr from 1787 to 1791 in a total of over 4,000 ton/yr of wrought copper. Naval demand rose from 300 to 1,000 tons/yr 1780 to 1790. Birmingham demand rose from 1,000 to 2,000 ton/yr 1780 to 1790, not including coinage (600 ton/yr).

Inflation in England

Between 1750 and 1800 inflation was 66%.

Between 1771 and 1800 inflation was 41%.[1] Then, as now, to retain the value of any capital, it had to be put to work or lose its value.

[1] Twigger.

British Copper Prices 1770-1805

In Pounds per ton[1]

1771-1779 Cornish Copper Standard

1780-1805 London Market FRTP

(Fire Refined Tough Pitch Copper)

The general price trend is upwards, fuelled by the decline of Parys Mountain and the rise in demand resulting from industrialisation, wartime activities and inflation. Note that the official price is notional and may vary from prices charged as mentioned in several of the events described. Soon after this period, the price fell back to vary around £110 per ton. Note that, for copper prices, the word ‘standard’ refers to the standard price and not the quality of the copper.

[1] Schmitz

Copper Price variables

When studying the economics of the copper industry, care is needed to check that any prices considered are relevant to the stage of manufacture and the added costs involved. There are four main prices, each of which has variations:

♀ Price to miners paid per ton of copper in the ore.

♀ Price ex Refinery including processing costs. This will also vary depending whether the product is ingot, cake or shot.

♀ Price ex Warehouse that includes the cost of financing stock and possibly cutting it to size for small orders.

♀ Price as semi-fabricated plate, sheet or wire for the manufacture of finished products.

Prices generally state the point of delivery including transport charges. The money actually paid rarely corresponds to the published figures. Sometimes a premium may be demanded for better than standard quality or packaging. More frequently, discounts are negotiated for regular commitments. Payment due dates can vary from spot cash on the day to three or even six months forward and the price may then be adjusted according to prevailing interest rates on the money outstanding.

Some Copper Kings

‘Copper Kings’ were a very rare occurrence; possibly less than one per generation. They are typified by love of hard work combined with excellent technical abilities and successful business flair. Besides close involvement with the copper industry, they had a wide variety of other interests that demonstrated a broad spread of abilities and an understanding of how events outside the industry might affect the future. They were set above others by popular acclaim based both on their entrepreneurial business record and their successful spread of other interests. Each had a dominant personality though not necessarily an aggressive one. For comparison with Wilkinson’s activities, brief details of some of the acknowledged ‘Kings’ are needed. The list starts with the most recent:

Sir Ronald Prain OBE (1907-1991)

♀ Born Chile, 1907 into a family with interests in nitrates.

♀ Came to Britain and began his career with metal merchants in London, showing great promise.

♀ He was head hunted by Chester Beatty of the Rhodesian Selection Trust Group and was soon appointed to the boards of their principal companies. ♀ He became Group Chief Executive in 1943 and in 1950 succeeded Sir Alfred Chester Beatty as chairman, a position that he held for 22 years until 1972. At the same time he retained a broad spread of other business and social interests.

♀ He was also a director of the International Nickel Company.

♀ He broke colour bars in Northern Rhodesian copper mines.

♀ Seeing that the copper could not last forever and that indigenous fuel was short, he promoted the growing of agricultural cash crops to diversify the economy of Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia.

♀ He had great foresight and wrote many papers on the economics of the copper industry world-wide, forecasting growth trends.

♀ For many years he was in demand to give the keynote paper at the start of any major copper conference, summarising the present status and future of the copper industry.

♀ For some years he was Chairman of Copper Development Association and then became honorary President until 1990.

♀ His enthusiastic membership of the Institute of Metals was commemorated by the establishment of the ‘Prain Medal’ annually to recognise work within the copper industry.

♀ He was elected ‘Man of the Year’ by the prestigious Copper Club of USA in 1964 as one of their very early obvious choices.

Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875-1968)

♀ Born in New York, he graduated as a mining engineer. Having started his career at Bingham Canyon copper mine and developed a technique for extracting copper from low grade ores. He was seconded to Katanga to open up Belgian copper mines.

♀ After his first wife died, he emigrated to Britain in 1910, becoming a British citizen in 1930.

Encouraged the development of Roan Antelope copper mine in 1925 leading to the foundation of the Rhodesian Copperbelt.[1]

♀ Raised more finance by setting up individual companies for each mine and became the acknowledged ‘Architect of the Rhodesian Copper Belt’.[2]

♀ “His wide engineering knowledge gained from long experience, coupled with his ability in financing and his keen insight and judgement, has been exercised to the full. It was due to his outstanding ability and enterprise that this has become one of the major copper fields of the world.”[3]

♀ Chairman Rhodesian Selection Trust

♀ He did important work in the provision of strategic raw materials 1939-1945.

♀ He encouraged talent, for example by taking on young Ronald Prain.

♀ Like John Wilkinson, he was an enthusiastic member of the Royal Society of Arts and endowed the annual Chester Beatty Memorial Lectures.

♀ He collected art and manuscripts assiduously, set up a library in Dublin and donated it all to Ireland in his will.[4]

The Wars of the Copper Kings 1876 – 1905

Three ‘Copper Kings’ were involved in the establishment of copper mining at Butte, Montana, that lead to the incorporation of Anaconda American Copper Co and the American Brass Co. The story starts with disputes over territorial claims on and under the surface and proceeds through all the rough and tumble of a classic Western. There were arguments over ore processing sites, transport routes and every other service needed for the industry.

Eventually law and order prevailed and the wealth of Butte that had initially needed Wall Street finance became a strong force in the heart of American finance. The main protagonists were William Andrews Clark, Marcus Daly and F Augustus Heinze of whom two eventually rose to become senators in the US Congress.

There are at least three books on this subject with evocative titles such as ‘War of the Copper Kings’ ‘Builders of Butte and Wolves of Wall Street, 1876 – 1905’ and ‘Anaconda’.[5] They still inspire the ambitions of young Americans.

Paul Revere (1734-1818) [6]

An American citizen of French Huguenot descent, he was born 1734 in Boston.

He served an apprenticeship with a silversmith in Boston and subsequently made a number of very fine pieces. Many of these still survive and command very high prices.

In 1756 he enlisted in the British Colonial Service and was commissioned a second lieutenant of artillery. Widowed at the age of 38 with six children, he remarried and had eight more.

By 1760 he was America’s best silversmith. Many items still survive and command very high prices.

In 1765 he was persuaded to join the ‘Sons of Liberty’ and lead protests against the British Parliament’s 1765 Stamp Act that imposed taxes on the unrepresented Colonists. He may have been present at the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

Famously, in 1775 he made the long, dangerous, night ride from Boston to Lexington Concord to give the warning: ‘The British are Coming!’ This inspired Longfellow to write the poem that begins: ‘Listen my children and you shall hear of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.’

In 1775 he set up mint to produce currency for the independent States of America.

By 1776 he was set up to make cannon, set up to make gunpowder. Became further involved helping in public life.

In 1792 he started casting church bells, making nearly 400 in all including at least one of a ton weight that is still in use.

A new copper foundry was established in 1800 together with rolling mills to make boiler plate and sheet for cladding naval ships. He was able to refine 1800 lb. of copper at one time using only wood for fuel.

He was accredited head of the copper industry in the US in 1804.

By 1812 he was making three tons of copper per week. Nearly 3½ tons was supplied to roof the State House in Boston, lasting over 100 years.[7]

He died in 1818. but his business did not then decline.

The Revere Copper Company was incorporated in 1828. For many years they also made copper domestic cookware and decorative ware in their factory in Rome, N.Y. The company is still in business.

To obtain expertise in its early years, the New England brass industry relied on signing up British brass workers clandestinely. They had to be smuggled aboard ship from England by being rolled up the gangplank hidden in barrels! Once near the American coast they re-entered the barrels and were floated ashore![8] Unlike some of his friends in New England, Paul Revere denied being involved.

John Vivian (1750-1826)

Born 1750 - d.1826

Born in Cornwall, he was a mine owner and metal dealer at a time when the ‘Ticket’ system of buying copper gave a great advantage to the smelters in Swansea. Sales of copper under this system are similar to those currently used on fish docks.

He set up a smelter in Swansea in competition with the existing refiners with the stated objective of stabilising copper prices for the benefit of the Cornish miners.

He joined the Cornish Copper Company cartel that was set up to keep copper prices up to benefit the Cornish miners and became Deputy Governor[9] and effectively the real manager of the company.

He was responsible for marketing the copper, had little success and has had much criticism, even as far as ‘gross negligence’.[10] Since the company had large stocks bought at high prices, he was presumably not in a good position to compete with the Anglesey mines and others selling at a lower price straight from the mines.

For several good reasons, he then took more interest in smelting, refining and manufacture which resulted in payments to miners going down.

He opened a warehouse for copper in Birmingham and set up separate manufacturing enterprises in Birmingham to make tokens and buttons, in competition with Boulton and Watt.

His name became unpopular therefore with many people in Cornwall, Swansea, Anglesey and Birmingham. Eventually he took over Parys Mine in 1811 in order to revive fortunes somewhat by introducing the Cornish system of deep mining to recover otherwise inaccessible ore. He did make the mines viable again, albeit at a lower tonnage output per year and is now celebrated locally in the Paris Mines port of Amlwch as a hero.

John Henry Vivian (1785-1855) his second son, born in Wales, later ran Vivian & Sons organisation in Swansea and Birmingham. He was not rated as a Copper King in his time but he did found a dynasty.

The copper mines at Parys Mountain in Anglesey were first worked during the Bronze Age but had been unused since Roman times. They were rediscovered in 1761 by Alexander Fraser and were being worked by Charles Roe of the Macclesfield Copper Company.

In 1769 Thomas Williams, a solicitor, was retained to act for one of the landowners, the Lewis family, in a dispute over the mining rights. [11] By the end of the litigation in 1778, Williams, the solicitor, had gained control of the Lewis holdings. He set up the Parys Mine Company with himself in control.

In 1780 he erected rolling mills and works at Greenfield, just East of Holywell in Flintshire, North Wales. A partnership was formed with John Westwood of Birmingham who had patented a good cold-rolling method that would help provide copper sheet and copper nails for Naval sheathing. Williams set up the Stanley Smelting Company with refineries at St Helens and Swansea. He also set up the Greenfield Company with the Cheadle Company’s refinery at Warrington and the brass works at Holywell. John Wilkinson had a one sixteenth share in this enterprise.

[1] Bradley, p88.

[2] Prain p28.

[3] President, Institute of Mining and Metallurgy on presentation of their Gold Medal in 1935, quoted by Bradley p99.

[4] http://www.cbl.ie/about/siralfred.html

[5] see books by Place, Glasscock and Marcusson

[6] Marcosson, pp17-21 and websites.

[7] http://64.90.169.191/innovations/1998/03/revere.html

[8] Marcosson Anaconda p169.

[9] Harris, p67.

[10] Hamilton, p179.

[11] Sources include Harris, Selgin, Hope and others.

During the same year, the Cornish Metal Company was set up by Boulton, Williams, Wilkinson, Vivian and others to sell copper jointly from Cornwall and Anglesey. Only a proportion of his Anglesey output was contracted to the Company. The rest he sold on the market cheaply which seems to have undermined the Company significantly. He was styled ‘Copper King’ by Matthew Boulton during this period.[1]

He set up copper refineries in competition with the main Swansea refiners. He was a very close friend of John Wilkinson[2]. In 1787 the Greenfield works was significantly enlarged to include Britain’s then largest rolling mill. Structural castings were supplied by John Wilkinson.[3]

1787 First ‘Druid’ tokens were struck for Williams, Wilkinson was not far behind in issuing his.

He became MP for Marlow in Berkshire where he had his mansion and Temple Mills copper works.

From 1791 to 1799 Williams gradually lost control of Cornish ores and suffered depletion of Anglesey ore quality. During its lifetime, the total output of copper metal from the Parys Mines was 130,000 tons.[4] With hindsight, it is evident that he could have controlled production rates better and retained his prosperity together with that of the Parys Mines by not selling all the copper that he could at reduced prices.

However, by 1799 he claimed to control a working capital of £800,000 in mines, refineries, fabricators and chemical works. Wilkinson had one sixteenth of the Stanley Co., which controlled the Middle Bank and Penclawdd smelting works in South Wales and the Stanley refinery in Liverpool.

As with Wilkinson’s enterprises, his business did poorly after his death. The mines were bought cheaply by John Vivian who successfully introduced Cornish deep mining technology and made the mines profitable again for some years.

Copper King Qualities

There are common qualities that become obvious when comparing the abilities of acknowledged Copper Kings. These include:

♀ Advanced technical skills and the ability to transfer them.

♀ Excellent financial foresight and acumen.

♀ Wide sphere of interests both in and outside the copper industries.

♀ Good at promoting themselves and their projects.

♀ Successful understanding of human relationships and political skills.

Above all these there is an essential that the individual must have qualifying achievements that are recognised to such an extent that he or she is nominated as ‘King’ by a recognised authority. Surely The Wilkinson Society has the status to nominate John Wilkinson as a ‘Copper King’ should it so wish. This would add to his existing status as a leading Ironmaster.

The attributes listed will be compared with the achievements of John Wilkinson. He was fortunate to be present at the beginning of the modern copper age and was able to make a significant contribution to its success.

The Modern Copper Age

To appreciate the magnitude of the work done to develop industrial production during the late 18th century it is useful to remember what a formative time it was. John Wilkinson and his contemporaries were working at just the right time to develop industry and the country’s prosperity at a vital stage during the Industrial Revolution.

The circumstances leading to the start of the modern copper age were summed very well by Sir Ronald Prain:

‘With the introduction of steam powered equipment was the beginning of the modern copper age, concluding a period of some thousands of years during which:

♀ Science was all hypothesis and no facts,

♀ Industry was all facts but no understanding and

♀ Time was of no consequence.’ .

(Prain, Sir Ronald, ‘Copper in Transition’ Opening address to the Metals Society Conference ‘Copper ‘83’, Amsterdam, 1983.)

Watt’s steam engine, he was in an ideal position to liaise with the users, many of whom owned copper mines. He could see financial opportunities that were too good to miss.

Wilkinson’s Interests in Copper

(Butler, Davis and others)

John Wilkinson had many interests in copper and some in brass at a variety of locations throughout the country.

This is a brief summary list. Further details follow for the main items.

Brassworks at Bersham and Bradley.[1]

Sales of iron castings and scrap to copper mines for steam engines, structures and the recovery of copper by cementation.[2]

Shares in Cornish copper mines such as Consolidated Mines, United Mines, Poldice, North Downs, Scorrier, Wheal Bussy, Tresaven and Chasewater.[3]

Shares in Mona Copper Mine, Anglesey[4]

Cornish Metal Company.

Copper refining capacity.

Birmingham Copper Co. Warehouse.

Greenfields Mills, Holywell, N Wales

Stanley Company, St Helens, Lancs.

Wharfs and warehouses at Chester and Rotherhithe, London.

Copper metal stock sales.

Copper Tokens for circulation in lieu of coinage.

John Wilkinson (1728-1808)

While this paper concentrates on the copper industry, many other events occurred at the same time. Circumstances will have helped guide the mind of John Wilkinson when he was making significant decisions. To help appreciation of achievements, this is a chronological list of some significant happenings that can be integrated with other biographical notes.

1728 - Born

1740 – Moved to BackBarrow

Educated at Kendal in the Lake District where the Mines Royal had been established to mine copper.

1754 - John married Ann Mawdsley.

1756 - Ann died, John moved to Broseley.

1757 - ‘Broseley ironmaster’ leased Old Willey furnaces.

1761 - Isaac Wilkinson’s Bersham works collapsed, he retired to Bristol, then still the centre of the brass industry.[5]

1763 - John married Mary Lee.

1766 – John set up Bradley ironworks in Bilton.

1776 - Wilkinson arranged the first sale of a Boulton and Watt engine to Cornwall for the West Wheal Virgin Mine and proposes that they go hard for the Cornish market.[6] Wilkinson approached Boulton and Watt for a partnership but was refused.[7]

1776 - His close friend Samuel More, Secretary of the Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce (now known as the RSA) joined Wilkinson in Birmingham for business meetings and was then Wilkinson’s guest in Broseley for a busy week of visits and discussions about iron works, steam engines and bridge building. More continued to help promote Wilkinson’s work until his death in 1797.[8]

In November 1779 Wilkinson visited Castle Head and travelled to the Coniston of the Lake District area as the guest of Mr Knott of Waterhead to see the Coniston copper-mining complex and assess its business potential.[9]

1780 By now he had met Williams and arranged to visit Parys mountain. He declared:

‘It’s a curious place and affords a large field for speculation.’[10]

1781 – He made a visit to Scotland with Thomas Williams for reasons not established but probably to evaluate copper mines.

1781 – Wilkinson used copper to roof his new house at Castlehead. It failed and was replaced with lead, presumably also from his own mills.[11] He might not have known that the usual reason for this type of problem is because of the unsuitable roofing techniques used rather than the copper quality.

1783 – First Boulton & Watt ‘rotative’ engine installed at Bradley.[12]

1785 – He was a key negotiator in setting up and financing the Cornish Metal Company with Boulton, Vivian, Williams and others.

1785 - Helped to form The United Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain with Messrs. Reynolds, Boulton, Watt, Wedgwood and others.[13]

1786, aged 58 and still being refused a partnership, there is some friction with Boulton but he still regards Watt with affection.[14]

1787 - Started minting copper tokens immediately after encouraging Thomas Williams to start production of his Anglesey tokens.

He accepted office as High Sheriff of Denbighshire.[15]

1795 – John’s brother William gave details of John’s ‘pirate’ steam engines to Boulton and Watt.[16] They had been built without payment of royalties. This will have reduced still further his chances of being offered a partnership.

Wilkinson, like Churchill and many other great men, did not need much sleep. Time spent asleep was time wasted. He preferred to lie and think usefully. He rested holding in his hand a steel ball, poised over a copper bowl. If he dropped off there was a clang of metal on metal that swiftly brought him back to beneficial thoughts.[17]

He was not known for philanthropy but was prepared to make furnishings such as the pulpit for a Bilston church, give money for a good cause[18] and to help out friends in financial problems.[19]

Quotations re John Wilkinson

There are many comments recorded regarding the actions of those mentioned in this paper. This is a selection that apply to John Wilkinson and are a help in judging reported actions.

All those qualities of character associated with Wilkinson’s business life in the Midlands are here again demonstrated, shrewd appraisal of the situation and a nice balance of advantage to either side, imaginative foresight, and again enormous boldness and confidence’.[20]

Wilkinson to Boulton:

“For God’s sake, endeavour to infuse a patriotic spirit in those that are to be the acting members in our metal company that the intention of so good an institution for the real interest of the copper trade be not defeated. There has been such egregarious mismanagement in the conduct of smelting as well as ignorance of it in the mining part that I am inclined to make another effort to save the company.”[21]

Boulton reported:-

“Mr Wilkinson hath acted with great spirit and firmness. He and Mr Williams have drove the Cornubians, and Bristol men also, before them like sheep, and kept them in a constant fever until all the foundations of our future plans were lay’d.”[22]

By November 1785, Wilkinson was able to say to Matthew Boulton

“All my adventuring cash is now engaged”[23] – and, we assume, giving a good profit.

‘Wilkinson’s tokens were a show of manufacturing power and independence’.[24]

‘He had a will of iron and a temper as hot as his furnaces but he was the man who made things viable’.[25]

As Cannadine said to a meeting of the Newcomen Society:

‘Britain has been one of the few great technological nations’, and we await the history which both describes that and explains it. All of which is simply to say that the history of technology has for a long time been much more than the history of machinery and engineering, important though those histories undoubtedly are.[26]

He implies that a combination of technical expertise with an ability to think laterally, financial acumen and a mastery of human relationships gives the recipe for success that is implied. John Wilkinson certainly had all these abilities. He could also appreciate the two-way interaction of his interests with current events affecting the prosperity of the nation. For a comparison with the entrepreneurs of this generation, I suggest that he would be the ‘Richard Branson’ of his day. The opportunities arising in the iron, copper and other industries of his day were similar to those in the much wider variety of industries today.

[1] Butler.

[2] Scrap iron plates were added to copper-rich water draining from the mine that had been lead to brick-lined precipitation ponds. Copper precipitated out leaving iron sulphate in solution. The iron was then precipitated out as valuable ochre pigment. Residual copper in the water was used to pickle timber before use in shipbuilding.

[3] Butler.

[4] Selgin,Ch2 p9.

[5] Davis, R.

[6] Dawson Ch5.

[7] Dawson Ch5.

[8] Dawson Ch 4.

[9] Dawson Ch 7.

[10] Butler.

[11] Dawson Ch7.

[12] Selgin, p50.

[13] Randall, J., Madeley, p64.

[14] Dawson Ch8.

[15] Dawson Ch11.

[16] Selgin, p52.

[17] Butler p457.

[18] Randall, J. Madeley, p109.

[19] Luter, Paul – At a meeting of The Chamber of Manufacturers in London, Wilkinson baled out William Reynolds with £100.

[20] Dawson Ch7.

[21] Butler.

[22] Harris p 61 quoting a letter from Boulton to Watt dated 22nd July 1785.

[23] Butler.

[24] Uglow p419.

[25] Uglow p253.

[26] D Cannadine.

Continued....

Topics continued as: Wilkinsons Interests in Copper

1775 Wilkinson’s Steam Engines

1785 The Cornish Metal Co

Shares in Copper Mines

1788 Birmingham Warehouse Company

Copper in Cast Iron

1787-1793 Wilkinson’s Copper Tokens

A Token Profit?

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

A s t.